The Blue Fox: A Novel Read online

Page 3

Fridrik paused when he saw the boy take this to a tumbledown shed, which leant up against another slightly larger outhouse in the back yard. There the boy opened a hatch and eased the tray inside. From the lean-to came a scrambling and snorting, a clatter and grunting. The boy snatched back his hand, slammed the hatch and hurried away, bumping straight into Fridrik who had entered through the gate.

‘What have you got there, a Danish merchant?’

He said this in a mock-serious tone to soften its severity. The youth gaped at Fridrik as if he were one of Baron Munchhausen’s moon men, then answered grumpily:

‘Oh, I reckon it’s that hussy what did away with her child last week.’

‘You don’t say?’

‘Yes, the one what was taken in the graveyard, burying the child’s corpse in Olafur “student” Jonsson’s grave.’

‘And why is she here?’

‘I ’spect the bailiff asked his cousin to hold her. They hardly dare put her in the gaol with the men, says Mother.’

‘And what’s to be done with her?’

‘Oh, I ’spect she’ll be sent to Copenhagen for punishment, and sold to the lowest bidder when she comes back. If she comes back.’

The lad darted a shifty glance around and pulled a small snuff horn from his pocket.

‘Anyhow, I’m not s’posed to talk about what I hear in the house ...’

He raised the horn to one nostril and sniffed with all his might. With that the conversation was at an end. While the cook’s son struggled with his sneeze, Fridrik went over to the lean-to. Squatting down, he pulled the cover from the hatch and peered inside. It was dim but the summer night cast enough blue light through the roof slats for his eyes to grow accustomed to the gloom, and he made out the figure of a woman in one corner. It was the prisoner.

She sat on the earthen floor with her legs straight out in front of her, hunched over the tray like a rag doll. In one small hand she held a strip of potato peel that she was using to push together fish-skin and bread, which she then pinched, raised to her mouth and chewed conscientiously. She took a sip from the tin cup and heaved a sigh. At that point Fridrik felt he had seen more than enough of the unhappy creature. He fumbled for the cover to close the hatch, bumping his hand on the wall with a loud knock. The figure in the corner became aware of him. She looked up and met his eyes; she smiled and her smile doubled the happiness of the world.

But before he could nod in return, the smile vanished from her face and was at once replaced by a mask so tragic that Fridrik burst into tears.

***

Fridrik unties the knot, winds the string round the fingers of his left hand, slides the coil over his fingertips and slips it into his waistcoat pocket. He unwraps the canvas from the bundle. Two packages of equal size come to light, wrapped in waxed brown paper. He lays them side by side and opens them. The contents of each appear to be the same: black wooden tablets, twenty-four in each pile. He turns over the tablets like cards from a pack, and notes that they are painted black on one side, white on the other; not all of them, however, because in one pile some of the tablets are black and green, while in the other they are black and blue. He scratches his beard.

‘Well, Abba-di, it’s quite something, this picture puzzle that you’ve carried through life ...’

And now a strange and intricate spectacle unfolds in the little parlour at Brekka in the Dale. The master of the house handles each piece of the puzzle with care, examining it from every angle; the green and blue faces have lettering on them – a sentence in Latin – which simplifies the game.

He begins the jigsaw.

Starting with the blue tablets.

Fridrik B. Fridjonsson studied natural history at the University of Copenhagen from 1862 to 1865. Like so many of his countrymen, he did not finish his degree, and for his last three years in Denmark he was a regular employee of the Elefant Pharmacy, then under the management of the pharmacist Ørnstrup, in Store kongsgade. There Fridrik worked his way up to the position of medical assistant, helping with the pharmacist’s catalogue of inebriants: ether, opium, laughing gas, fly agaric, belladonna, chloroform, mandragora, hashish and coca. In addition to being used for various cures, these substances were greatly favoured by the lotus-eaters of Copenhagen.

The lotus-eaters were a group who modelled their way of life on the poetry of French writers such as Baudelaire, de Nerval, Gautier and de Musset. They threw parties – which gave birth to many rumours, but few attended – at which narcotic plants bore away the guests swiftly and sweetly to new worlds, both in flesh and in spirit. Fridrik was a frequent guest at these gatherings, and once, when they stood up from their ether-driven roller-coasters, he announced to his travelling companions:

‘I have seen the universe! It is made of poems!’

‘Spoken like “en rigtig Islænding”, a true Icelander,’ said the Danes.

Fridrik’s trip to Iceland in the summer of 1868 was, on the other hand, a far more earthbound affair. He had come to sell up his parents’ farm following their deaths from pneumonia, nine days apart, that spring. There were no assets to speak of: the remote croft of Brekka, the cow Crooked Horn, a few scrawny ewes, a fiddle, a chessboard, a bookcase, his mother’s spinning wheel and the tom cat Little Frikki. So the plan was to make his stay brief; it wouldn’t take long to sell the livestock to the neighbours, pay off the debts, pack up the furnishings, hang the cat and burn the farm buildings which were crumbling into the hillside, to the best of Fridrik’s knowledge.

And this is what he would have done if the universe had not thrown up an unexpected riddle in a filthy outhouse one sunny night in June.

***

The wooden tablets play in Fridrik’s hands; what had looked like an incomprehensible puzzle now guides his fingers. It’s as if the riddle is solving itself by magic; without conscious intent the man lays one tablet against another and the moment their edges touch, one slides into the other’s groove and then will not be budged; and so on and on, until the blue tablets have formed a base, while the others are the walls and gable-ends of what resembles a long, quite deep, trough; white-walled within, black without.

And the sentence on the base resolves itself: ‘Omnia mutantur – nihil interit’. Fridrik laughs scornfully: ‘All things change – nothing perishes’. He can’t imagine what cunning craftsman could have given Hafdis this object, choosing for her a quotation from Ovid, no less.

There is a lowing from the back of the house.

The riddle-solver wakes from his thoughts; Crooked Horn the Second is demanding attention. Fridrik puts down the creation and hurries to the byre; he hasn’t yet got the hang of the new household arrangements at Brekka; the animals used to be Abba’s concern.

***

Twenty-riksdaler stipends to students at the University were encumbered with the task of accompanying friendless folk to the grave. Fridrik performed this dreary duty like anyone else, but as he was a hopeless bibliomaniac and forever in the red with Høst the bookseller, he welcomed the chance to take the night watch at the city mortuary. While there he took on yet another job – that of translating articles from foreign medical journals for a thick-witted but well-to-do pathological anatomy student from Christiania.

Fridrik sat many a night by a smoking lamp, translating into Danish descriptions of the latest methods of keeping us poor humans alive, while on pallets around him lay the corpses, beyond any aid, despite the encouraging news of advances in electrical cures.

In the third volume of London Hospital Reports, 1866, Fridrik read an article on the classification of idiots by J. Langdon H. Down, a London doctor. The article was an attempt to explain a phenomenon that had long puzzled people: the fact that white women sometimes gave birth to defective children of Asiatic stock. The doctor conjectured that the mother’s illness or a shock during pregnancy might have caused the child to be born prematurely. This could happen anywhere in the well-documented developmental stages of the foetus: fish–lizard–bird–dog�

��ape–Negro–yellow man–Indian–white man, but seemed most common at the seventh stage.

Down’s Mongoloid children had therefore not attained full development; they were doomed to be childish and meek all their lives. But like other members of inferior races, with kind treatment and patience they could be taught many useful skills.

In Iceland they were destroyed at birth.

Unlike other types of cretins, where it cannot be seen until too late that they do not have their full wits, no one could fail to see that a Down’s child was made according to a different recipe from the rest of us, even of different, alien ingredients: it had coarser hair, a yellowish complexion, stumpy body, flabby skin and eyes slanted like slits in a canvas.

No witnesses were needed; before the child could utter its first wail, the midwife would close its nose and mouth, thereby returning its breath to the great cauldron of souls from which all mankind is served.

The child was said to have been stillborn and its body was consigned to the nearest priest. He confirmed its nature, buried the poor creature and that was the end of the story.

But there were always some such unfortunate infants that managed to survive. It happened in godforsaken out-of-the-way places where there was no one to talk sense into the mothers who thought they could cope with the children, odd though they were. Then of course they got lost, wandering off in their ignorance, leaving their bones on mountain paths, turning up half-dead in the summer pastures or simply stumbling into the lives of strangers.

And as the poor wretches didn’t know who they were or where they had blown in from, the authorities would settle them on whichever farm they happened to have ended up at.

The farmers were greatly annoyed by these ‘gifts from heaven’, and the household found it degrading to have to share their sleeping quarters with a defective.

***

There was no question that the unfortunate girl imprisoned in the bailiff of Reykjavik’s kinsman’s back yard was one of those Asiatic innocents who owned nothing but the breath in her lungs.

Wiping the food off her hands, she embraced the young man’s head as he wept in the chicken-hatch, comforting him with the following words:

‘Furru amh-amh, furru amh-amh ...’

Twilight deepens in the valley; the afternoon night begins its journey up the slopes. The darkness seems to flow from the open grave in the western corner of the churchyard at Botn, as if the shadow grows there first, before darkening the whole world. It’s a near thing with the light: four men appear in the church doorway with a coffin on their shoulders, the parson hard on their heels, followed by several of those black-clad crones who are never ill when there’s someone to be seen to the grave. The funeral cortège proceeds rapidly, as if in a dance, their short steps breaking into quick variations, for the churchyard path is as slippery as glass, although Halfdan Atlason had been sent to break up the surface while they sang over his lady friend in church. Now he stands by the lych-gate, tolling the funeral bell.

A gust carries the copper song down the valley into Fridrik’s parlour where he hears its echo – no, it’s the knowledge that Abba’s funeral is taking place at this moment that has rung the tiniest bell in his mind.

He’s putting the finishing touches on the puzzle’s companion piece; it’s the exact image of the other, except that its base is green, with a different Latin tag. This is also by the author of Metamorphoses, translating as: ‘The burden which is well borne becomes light’.

The moment Reverend Baldur’s pallbearers lower the coffin into the black grave at Botn, it not only becomes pitch black in the valley but light is shed on the contents of the parcel that Hafdis Jonsdottir brought with her north to the Dale, when Fridrik B. Fridjonsson, favourite student of a close kinsman of the bailiff, got her absolved from the charge of exposing her child, on the grounds of ignorance, and on condition that she would remain in his care for as long as she lived.

Yes, if the two halves of the puzzle were laid together they would form an artfully crafted, highly polished coffin.

***

When Fridrik B. Fridjonsson rode north with his peculiar maid-servant and settled on his father’s estate at Brekka, the parish of Dale was served by a burnt-out priest popularly known as ‘Reverend Jakob with the pupil’ Hallsson, who as a child had taken out one of his eyes with a fishhook.

This incompetent minister was so used to his parishioners’ boorishness – scuffles, belches, farts and heckling – that he affected not to hear when Abba chimed in with his altar service, which she did both loud and clear and never in tune. He was more worried that the precentor would drown in his neighbours’ spittle. This fellow, a farmer by the name of Gilli Sigurgillason from Barnahamrar, possessed a powerful voice and sang in fits and starts, gaping so wide at the high notes that you could see right down his gullet, and the congregation used to amuse themselves by lobbing wet plugs of tobacco into his mouth – many of them had become quite good shots.

Four years later Reverend Jakob died, greatly regretted by his flock; he was remembered as ugly and tedious, but good with children.

His successor was Reverend Baldur Skuggason, who introduced a new era in church manners to the Dale. Men sat quietly on the benches, holding their tongues while the parson preached the sermon, having learnt how he dealt with rowdies: he summoned them to meet him after the service, took them round the back of the church and beat the living daylights out of them. The women, meanwhile, turned holy from the first day and behaved as if they had never taken part in teasing ‘the reverend with the pupil’. They said it served the louts to whom they were married or betrothed right, they should have been thrashed long ago; for the new parson was a childless widower.

Gilli from Barnahamrar now sang louder than ever, at the speed of a piston, with mouth gaping wide. But Fridrik was asked to leave Abba at home: the word of God must reach the ears of the congregation ‘uninterrupted by the ravings of an idiot’, as Reverend Baldur put it after the first and only time Abba attended one of his services.

There was no shifting him from this position; he would not have her anywhere near him. And none of the newly civilised and well-thrashed parishioners would speak up for a simple woman who knew no greater happiness than to dress up in her Sunday best and attend church with other people.

After this, Fridrik and Hafdis had few dealings with the folk of Dale. Halfdan Atlason sneaked a visit to Abba when he could. But the parson of Botn took a wide detour when he met them on the road.

***

The churchyard at Botn stands on the banks of the River Botnsa. This is a middling-sized, smooth stream, of a good depth and high-banked, bordered by spongy patches of marsh, with plenty of good peat land and enough of that deceptive surface rust. After a winter of heavy snow the river runs wild, bursting its banks with such demonic force that the dirty-grey melt water surges out of its course, flooding the marshes and forming lakes in the graveyard, leaving the church stranded on an island in its midst. The water-ringed house of God remains cut off until the graveyard has swallowed enough of the mountain milk for the water to just cover a maiden’s ankle; by then the sanctified ground is drunk and wobbles underfoot until well into summer.

After such fits in the Botnsa, the riverbank gives way and the churchyard crumbles into the river. Then it is clear that nature has treated the dead with so little respect that all is reduced to a mush: teeth and coccyx, fingers and toes, adults and children, lower jawbones and scalps, buttocks here, a woman’s pelvis there, a vertebra from this century, a man’s paunch from the last but one.

No, one couldn’t exactly say that ‘the Lord’s garden’ here in the Dale was cultivated; and men had to be true neighbours to be willing to revisit their neighbours in this condition.

So it was that on Monday 8th January 1883, Reverend Baldur performed the funeral rites on the company that Herb-Fridrik considered worthy of those who could not bring themselves to allow a simpleton to sing out of key with her parish priest: a quilt cover s

tuffed with sixty-six pounds of cow dung, the skeleton of a decrepit ewe, an empty aquavit cask, some rotten barrel staves and a mouldy urine tub.

Abba deserved a different soul-mate, fairer earth.

Ghost-sun is a name given by poets to their friend the moon, and it is fitting tonight when its ashen light bathes the grove of trees that stand in the dip above the farmhouse at Brekka. This little copse was the loving creation of Abba and Fridrik, and few things made them more of a laughing stock in the Dale than its cultivation, though most of their endeavours met with ridicule.

The rowan draws shadow pictures on the snow crust; there’s a low soughing in the naked boughs and the odd twig still bears a cluster of dried berries that the birds overlooked last year.

Fridrik toils slowly up the slope; he has a woman’s body in his arms. In the middle of the grove is a freshly dug grave; on the edge of the grave stands an open coffin. The man approaches the coffin and lays the body inside. Then he hurries back, but the moon remains.

Hafdis is well equipped for her final journey. She’s dressed in her Sunday best and great care has been taken with every aspect of her costume: on her head sits a cap with a long tassel and an oft-twisted silver tube; around her neck is a violet silk scarf; her jacket is of English cloth and the embroidered borders of her bodice are visible beneath; her apron is sewn from rose damask and the buttons, cast in white silver, bear an elaborate ‘A’; her skirt is striped with cross-stitched velvet bands and her legs are encased in red socks and high black stockings; her shoes are of heather-coloured calfskin with white stitching; and on her hands she wears black mittens, with roses in four colours knitted on the backs.

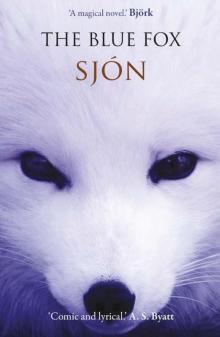

The Blue Fox: A Novel

The Blue Fox: A Novel From the Mouth of the Whale

From the Mouth of the Whale The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North Moonstone

Moonstone CoDex 1962

CoDex 1962 The Whispering Muse: A Novel

The Whispering Muse: A Novel The Whispering Muse

The Whispering Muse The Blue Fox

The Blue Fox