The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North Read online

Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Ted Hodgkinson and Sjón

Sunday

Naja Marie Aidt (Denmark)

The Man in the Boat

Per Olov Enquist (Sweden)

In a Deer Stand

Dorthe Nors (Denmark)

The White-Bear King Valemon

Linda Boström Knausgaard (Sweden)

The Author Himself

Madame Nielsen (Denmark)

A World Apart

Rosa Liksom (Finland)

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat

Johan Bargum (Finland)

Weekend in Reykjavík

Kristín Ómarsdóttir (Iceland)

The Dogs of Thessaloniki

Kjell Askildsen (Norway)

From Ice

Ulla-Lena Lundberg (Åland Islands)

“Don’t kill me, I beg you. This is my tree.”

Hassan Blasim (Finland/Iraq)

From Zombieland

Sørine Steenholdt (Greenland)

Avocado

Guðbergur Bergsson (Iceland)

Some People Run in Shorts

Sólrún Michelsen (Faroe Islands)

1974

Frode Grytten (Norway)

May Your Union Be Blessed

Carl Jóhan Jensen (Faroe Islands)

San Francisco

Niviaq Korneliussen (Greenland)

Notes from a Backwoods Saami Core

Sigbjørn Skåden (Saami-Norwegian)

Author Biographies

Copyright Acknowledgements

About the Authors

About the Publisher

Copyright

Introduction

TED HODGKINSON AND SJÓN

THE NORTH CONJURES epic storytelling. It is the birthplace of the saga, where stories of human survival have long been sculpted by the region’s raw elements, as in turn they have shaped its varied landscapes, from sheltering forests to islands lashed by unforgiving seas. The ancestry of this tradition can be found in many-volumed novels that detail struggles against the headwinds of the modern-day elements, and also in the vicissitudes of Nordic noir, which keep us in suspense, season after season. More than recounting feats of endurance, the storytelling of the region is also alive to the possibilities of human transformation, rooted in the metaphysical world of folklore and fairy tale. The contemporary Nordic short story is a crucible in which these properties are fused together, capturing a quest for survival while prising open, in the space of just a few pages, potential for radical change. These are timely qualities in a world on the brink, in which we need to find ways of reimagining our relationship to our natural surroundings, ourselves and each other.

Sjón is an author uniquely attuned to these storytelling frequencies, who in his own writing across many forms creates historical epics in miniature, focusing on moments of profound transformation, through an often surreal lens. A priest hunts a mysterious blue fox across the stark winter-scape of nineteenth-century Iceland. Or in his most recent novel, a young boy captivated by cinema awakens to his true identity as Spanish flu ravages Reykjavík in 1918. Sjón has brought his own distinctive vision to this first ever selection of short stories from the Nordic region in English, published to coincide with the Southbank Centre’s Nordic Matters series and the London Literature Festival. Our selection encompasses writers from across generations of each literary culture, to present a prismatic perspective of each place, refracting a broad range of literary styles and human experience. The overall balance of genders reflects a region which has produced some of the finest writers of either gender at work today, though it’s also especially notable that many of those from the younger generation are women breathing fresh life into the literature of their homelands, including Dorthe Nors, Linda Boström Knausgaard and Niviaq Korneliussen. While in recent years many Nordic novelists have found their way into English translation, relatively few of those writers who have focused on the short story have made that same journey—this anthology aims to help close those gaps and create openings into a revelatory world of storytelling.

To introduce the selection, I begin by asking my co-editor Sjón what he sees as the cultural and literary connections between the eight distinctive Nordic lands of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, the Faroe Islands, Åland Islands, Greenland and his native Iceland.

*

Sjón, the Nordic region covers a vast and varied terrain, both geographically and culturally. What are the things which bind it together? What are the elements that make up a Nordic identity? And after editing this anthology, what have you discovered about the literary links between the writers of the North?

The Nordic identity question is one Nordic authors are repeatedly asked in interviews or on the panels of literary festivals; especially abroad and especially in the context of the Nordic Council’s Literature Prize. Their usual reaction to it is to be annoyed at hearing it again, before they answer that there is no common identity; that the literatures of each country have developed in their own specific ways; and so on. But as I take it, the question is really not about our own contemporary literary output but the deeper currents that run under the whole social make-up of the North. So I always try to answer it positively.

The fact that we share history, both cultural and political, that goes back more than a millennium means our societies—which in the beginning seem to have all been Germanic and heathen, and speaking variants of Old Norse—have been introduced to great historical changes at the same time and had to react to them from that common ground. So the region’s movement from the Norse religions to Catholicism, from Catholicism to the Protestant Reformation, from the Reformation to Enlightenment via the Renaissance, from monarchy to democracy and then on to twentieth-century trends in ideologies, art movements and empowerment of social groups, could therefore be seen as one, making us a single culture with regional variations.

The long shared political history is, of course, also a story of wars, invasions, defeats, colonization and the fight for independence among those countries—and thereby of narratives about individuals and communities caught up in those events at the same time while in different parts of the North.

By editing this anthology with you, Ted, I have become even more sure than ever before of how deep the common Nordic roots lie and how consistent authors in the North are in collectively nurturing and feeding from them.

From Johan Bargum’s haunting story in which a father believes he is a dog, to Hassan Blasim’s fierce and funny tale of a tiger who is writing a crime novel and drives the 55 bus in Helsinki, to Dorthe Nors’s spooky story of a man with an injured ankle waiting by a deer stand as darkness falls, many of the stories here capture a moment of transformation, or characters caught on the threshold between worlds. Your writing is also deeply alive to the possibilities of transformation. What makes Nordic writers so imaginatively drawn to the metaphysical, or even the magical?

I think that within much of Nordic literature there are two main tendencies at play—the naturalist school and the folk tradition or diverse common-folk’s belief systems—and since the beginning of modernity one can see them used together or combined in different measures in most of the best short stories and novels from the region. The naturalists’ legacy of writing socially relevant stories—and their faith in the author’s power to be a voice of change by revealing society’s ills with literary means—is still there and responsible for the strong humanist foundation shared by the stories readers will find in this anthology. A part of that humanist worldview is respecting what folk

stories have to offer as literature and as the means to understand the universe and man’s place in it. And, as you know, once you are there—in a forest of stories, on an island of too many tales, in a city of sorrowful rhymes—you are in a world where metamorphosis and transcending the borders of the “real” and the “true” are more than just possible, they are tools of survival in harsh natural surroundings or a failing community. Today this can be seen in narratives about changing identities or new sexualities.

Another strong factor in Nordic literature is the early input of the avant-garde in most of the countries—surrealist poetry and the modernist novel—which on the one hand has resulted in a relentless questioning of the realist method, and on the other in renewing the ways authors can use elements from folk culture in their writing. Add to all of this the influence of diverse strands of Protestant and radical political thinking on Nordic authors and you have a heady brew. I’ll stop here, but I am glad you mentioned Hassan Blasim as he and other authors who have come to our countries in the North from faraway places around the globe are already creating new challenges for Nordic literature and moving it forward with their own stories from abroad and within, with references to shape-shifters we couldn’t even dream of.

Why do the stories we tell matter in a world on the brink?

Even though our Nordic welfare states are today as modern/post-modern as they can possibly can be, the great works of twentieth-century Nordic literature makes us keenly aware that we are just a generation or two—maybe three, four, I tend to forget as I get older—away from life lived in hardship brought on by unjust and unforgiving societies. This is a literary and social heritage I don’t hesitate to insist no Nordic writer can escape from and which can be found at the root of all the stories in this anthology, even when it is not directly noticed; no matter if their authors are born sixty-one years apart, in 1929 like the Norwegian Kjell Askildsen or in 1990 like Niviaq Korneliussen from Greenland.

But what they also share, apart from this grounding in social awareness, is the need to tell a good story (melancholic, absurd or grim as it may be) with means both tested and newly invented. Because who has the patience to read a tale from small places at the edge of the globe or on the margins of communities if it isn’t told with wit—dark and dry, of course, we are Nordic—precision and restrained empathy for its characters?

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat travels with diverse stories in its pockets and even in its linings. It comes to its readers from the affluent North that tops every global survey of happiness and equality, but on closer inspection it will reveal itself to be worn at the elbows, patched up here and there. In our present world of conflict and climate change, it offers what literature has always had to offer—the few moments of warmth that come from sharing a story, a chance for people to compare their fates, to discover their common humanity and to ask for stories in return.

SUNDAY

NAJA MARIE AIDT

IT WAS COMPLETELY STILL ON the terrace in front of the house where Iben was sitting on a bench with her back against the wall, enjoying watching the children bounce on the trampoline. She could hear Peter shouting something, making the children squeal with delight. It was such a beautiful day. The September sun crashed down from a cloudless sky. The cat snuck under the bench. They had all sat there eating breakfast a little while ago, and now Kamilla was inside doing the dishes with the girls. Iben closed her eyes and leaned her head back. She remembered a sad and pretty song that had always made her cry with joy when she was young. She whistled the opening lines to herself. Then someone was pulling on her sleeves. It was her son wanting to go down and throw stones into the pond at the far end of the yard. She got up and took him by the hand.

Mosquitoes swarmed over the water. She threw a stick in and told the boy that it was now sailing out into the wide world. But the boy replied that it would never come up from that mud-hole again. The girl bounced light as a feather up and down on the trampoline. Peter stood near them smoking. Then Kamilla came out on the balcony with a camera. “Smile!” she shouted. Iben and the boy went over to the others, and then all four of them looked up at her. Peter made the children say cheese. Kamilla suggested that they go to the bakery to get some pastries.

They put both children in the pram. The neighbourhood was abuzz with Sunday and late summer; people were busy with garden work and afternoon coffee, a group of teenagers played ball, and some younger boys sat in an apple tree and threw rocks at a small group of girls playing hopscotch. The strong orange afternoon light made everything look clear and almost surreal. Peter’s brown eyes shone like illuminated stained glass, and she began to wonder about the yellow spot she thought he had in his left eye, which he definitely once had, but that she hadn’t noticed in a long time.

“What a day!” he said, pushing her to the side so he could take over the pram. “And here we are taking a stroll,” she said. “Yeah,” he said, “here we are taking a stroll.”

The bakery was closed so they had to go to the petrol station at the other end of town. They walked in step, side by side. They talked a little about the older girls. Iben said they should probably start thinking about birth control for the oldest one. “For Christ’s sake, she’s only fourteen!” Peter said, raising his voice. Iben told him that the youngest one was still lagging behind in school and was getting terrible grades. “You have to go over her homework with her more,” she said. Peter snorted, “Birth control!” She looked up at a poplar tree and caught sight of a squirrel. She counted to ten slowly to herself. A large BMW was parking in front of them. “They’ve got too much fucking money around here,” said Peter, stepping testily to the side as the car backed over a large puddle. “We’ll never have that problem,” she said. Then he stopped at the hotdog stand and got the children hot dogs with ketchup and relish. He bought a hamburger for himself. She had a bite, and he wiped ketchup from her cheek. They shared a pint of chocolate milk. “Like the old days,” he said, with his mouth full of relish, “before we learned how to cook.” “When we lived on fried cod roe,” she said. “With mushy potatoes,” he said. “Yeah, and that was because you insisted on cooking them in the duvets, like your mother taught you, but you can only make rice pudding that way.” Then the girl began to cry and he pulled her out of the pram and swung her around. That scared her and she gulped down most of her hot dog. Iben hurried to walk ahead. It was such a beautiful day.

They stood in the convenience store at the petrol station, each with a child in their arms—he wanted a lemon pound cake and she, a marzipan cake. They ended up buying both. On the way back, he wanted to have a cigarette. “Why didn’t you buy some yourself?” she asked. “I didn’t think of it,” he answered, as she rooted around in her pocket for a match. She sighed. He began to hum an old pop song, and soon he was screaming it at the top of his lungs. People in their gardens turned to look at them. The girl fell asleep. The light grew deeper in colour, redder, and she said she’d heard that at some point people who are dying blaze up, become their old selves again, full of energy, so that their loved ones almost think that they’re about to come round, and then suddenly they die; this feels unexpected and so it comes as a big shock. Peter threw his cigarette over a wrought-iron gate. “That’s what they deserve,” he said. “Did you hear anything I said?” she asked. “Rich bastards!” he yelled. The man passing them on the path in a polo shirt and tan trousers stared condescendingly, first at them, then at the worn pram, which they had bought for the older girls.

When they got back to Kamilla’s house, the girls came bounding up the garden path. The eldest smacked the garden gate into Peter’s stomach. Kamilla came walking across the lawn with a coffee pot. “They’re going down to get the dog at Madsen’s,” Iben said. “What the hell is the dog doing at Madsen’s?” Peter asked. “They used to have a dog salon, Peter. You know that Mum and Dad always got Bonnie trimmed there.” Peter looked at Iben with an expression that made her laugh hysterically. “Peter! It’s a terrier,” she said

, miffed. “It needs to be trimmed once in a while, and Madsen does it on the cheap.” Iben took the boy out of the pram and walked a little way away. “A terrier!” she heard him say, and she began to titter and pushed herself forward in order not to laugh outright. She could feel that Peter was watching her. She heard him laugh loudly. “You two!” said Kamilla, who was disappointed about the pastries. She had been looking forward to cream puffs. And it was cold now, even though all three of them were wrapped in duvets. Iben still didn’t dare look at Peter. Laughter stirred in her throat; for a moment she was afraid she’d begin to cry. The boy stuffed a large piece of lemon pound cake in his mouth. The girl sighed in her sleep. Peter said, “Can you take the girls next weekend? Dorte’s parents are coming to stay with us.” “Poor you,” said Iben, wiping the boy’s mouth. He was busy pulling apart a dead flower. A cold wind blew the petals onto the grass. She had finally got control of herself. “I thought you were coming to Aunt Janne’s birthday on Sunday,” said Kamilla. “Sorry,” said Peter, shooting Iben a look, who suddenly had to put her hand to her mouth to hold back the laughter. Kamilla leaned back in the chair. “How long have you two been divorced?” she asked. “Seven years in November,” said Iben, looking at Peter. “Isn’t that right?” He nodded. “Seven years in November,” he repeated. The sun shone right in his eyes, and she finally caught sight of the yellow spot in the brown. She felt strangely relieved. She knew it was there somewhere.

TRANSLATED BY DENISE NEWMAN

THE MAN IN THE BOAT

PER OLOV ENQUIST

THE STORY, as I recounted it to Mats …

This all took place the summer I was nine. We lived by a lake called Bursjön, a fine lake, large, with small islands. I was nine and Håkan was ten. A river passed through the lake, entering at the northern end and flowing out at the southern. It came from far up in Lappmarken, and in spring timber was floated downstream. In May I could see it all from our window: the lake filling with logs, lumps of ice and ice floes, the timber slowly drifting southwards, and then, one day that same month, finally disappearing.

The Blue Fox: A Novel

The Blue Fox: A Novel From the Mouth of the Whale

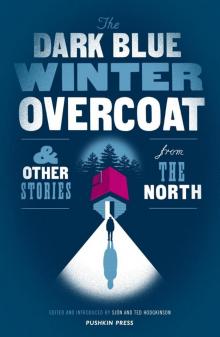

From the Mouth of the Whale The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North Moonstone

Moonstone CoDex 1962

CoDex 1962 The Whispering Muse: A Novel

The Whispering Muse: A Novel The Whispering Muse

The Whispering Muse The Blue Fox

The Blue Fox