The Blue Fox Read online

Page 2

His breeches are hitched right up to his crotch, his coat is far too big or far too small, depending on how you look at it, and his knitted hat is tied so tightly under his chops that he cannot have done it himself; on his hands he wears three pairs of mittens, making it almost impossible for him to hold the reins of the hairy nag on which he sits.

This is the mare Rosa. She champs her bit impatiently. It is her legs that have carried them here. When you look back you can see her hoofprints running from the parsonage at Dalbotn, down over the fields, along the river, across the marshes, up the slopes, to the place where she is now standing, waiting to be relieved of her burden.

Ah, now the man clambers down from her back.

And his true shape is revealed: he is extraordinarily low-kneed, big-bellied, broad-shouldered and abnormally long-necked, and his left arm is quite a bit shorter than his right. He stamps his feet, beats his arms about himself, shakes his head and snorts.

The mare flicks her ears.

‘Sea-hail porpoise?’

The man scrapes the snow from the farm door with his stubby arm:

‘Can it be?’

He knocks on the door with his good hand and feels the blood rushing to his fist. It’s cold. Perhaps he’ll be invited inside?

The shadow of a man’s head appears in the frost-patterned parlour window, and a moment later the inner door can be heard opening, then the front door is thrust out hard. It clears away the pile that has collected outside overnight, and the cold visitor, retreating before it, falls over backwards, or would do if the snow allowed. When he is done falling, he sees that the man he has come to find is standing in the doorway: Fridrik B. Fridjonsson, the herbalist, farmer at Brekka, or the man who owns Abba. The visitor’s own name is Halfdan Atlason, ‘the Reverend Baldur’s eejit’.

Now he gulps like a fish but says not a word, for before he can recite his piece, Herb-Fridrik invites him to step inside.

And to that the eejit has no other answer than to do as he is asked.

They enter the kitchen.

‘Take off your things.’

Fridrik squats, opens the belly of the tiled stove and puts in more kindling. It blazes merrily.

It’s warm here, a good place to be.

The eejit bites his thumbs and tugs off his mittens before beginning with trembling hands to struggle with the tight knot on his hat strings. He’s in difficulties, but his host frees him from his prison. When Fridrik pulls off his guest’s coat a bitter stench is released. Fridrik backs away, nostrils flaring.

‘Coffee ...’

It was always the same with the Dalbotn folk; they sweated coffee. The Reverend Baldur was too mean to give them anything to eat, pumping them instead from morning to night full of soot-black, stewed-to-pulp coffee grounds. Fridrik takes a firm hold of Halfdan’s hands; the tremor that shakes them is not a shiver of cold but a nervous disorder – from coffee consumption.

He releases the man’s paws and invites him to sit down. Taking a kettle from a peg, he fills it with melted snow and places it on the hotplate on top of the stove. He points to the kettle and says firmly:

‘Now, you keep an eye on the water; when the lid moves come and tell me. I’ll be in the parlour nailing down the coffin lid.’

The eejit nods and turns his eyes to the kettle. Herb-Fridrik brushes a hand over his shoulders as he leaves the kitchen. After a moment the sound of hammer blows comes from the next room.

The eejit stares at the kettle and stove in turn, but mostly at the stove. It is a widely famed wonder of technology that few have set eyes on. The metal pipe, which rises from the stove, runs up the wall into the parlour, and from there up to the sleeping loft, warming the house, before poking out through the turf-roof and releasing the smoke into the open air. But first and last it is the handpainted china tiles that enchant: brightly coloured flowers sprawl here and there about the body of the stove, nimbler than the eye can follow. Halfdan rocks in his seat as he traces one flower spray, which winds under this one and over that, all the way up to the kettle.

The kettle, yes, just so, he’s keeping an eye on it. The water spits as it jumps around between the bottom of the kettle and the glowing hotplate.

Fridrik the herbalist is the man who owns his Abba; that is, Hafdis Jonsdottir, Halfdan’s sweetheart. Fridrik and Abba live together, just the two of them, at Brekka – until she marries Halfdan, then she’ll come away with him. But where might she be today? He twists his elongated neck to peer over his right shoulder.

In the parlour Fridrik is hammering the last nail into the coffin lid. Halfdan calls in to him:

‘I-Hi’m here to fe-fetch the female corpse ...’

The bleak wording takes Fridrik aback. That’s Parson Baldur talking through his manservant. The parsonage servants parroted the priest’s mode of speech like a parcel of hens. No doubt one might have called it laughable, had it not been all of a piece, all so ugly and vile.

‘I know, Halfdan old chap, I know ...’

But he is even more startled by what the eejit says next:

‘Whe-here’s h-his A-Abba?’

The water boils and the kettle lid rattles – it sputters slightly at the rim.

‘B-boiling,’ sniffs Halfdan, and it is the first sound he has uttered since Herb-Fridrik told him that his sweetheart Abba was dead, that she was the female corpse the Reverend had sent him to fetch, and that today the coffin he saw there on the parlour table would be lowered into the ground in the churchyard at Dalbotn. The news so crushed Halfdan’s heart that he burst into a long, silent fit of weeping and the tears ran from his eyes and nose, while his ill-made body shook in the chair like a leaf quivering before an autumn gale, not knowing whether it will be torn from the bough that has fostered it all summer long or linger there – and wither; but neither fate is good.

While the man grieved for his sweetheart, Fridrik brought out the tea things: a fine hand-thrown English china pot, two bone-white porcelain cups and saucers, a silver-plated milk jug and sugar bowl, teaspoons and a strainer made of bamboo leaves. And finally a tea caddy made of planed, oiled oak, marked: ‘A. C. PERCH’S THEHANDEL.’

He takes the kettle from the hob and pours a little water into the teapot, letting it stand a while so the china warms through. Then he opens the tea caddy, measures four spoonfuls of leaves into the pot and pours boiling water over them. The heady fragrance of Darjeeling fills the kitchen, like the steam that rises from newly ploughed earth, and there is also a sweet hint, pregnant with sensuality – with memories of luxury – that only one of them has known: Fridrik B. Fridjonsson, the herbalist from Brekka in his European clothes; in long trousers and jacket, with a late Byronesque cravat round his neck.

Likewise the scent raises Halfdan’s spirits, causing him to forget his sorrow.

‘Wh-what’s that c-called?’

‘Tea.’

Fridrik pours the tea into the cups and slips the cosy over the English china pot. Halfdan takes his cup in both hands, raises it to his lips and sips the drink.

‘Tea?’

It’s strange that so good a drop should have such a small name. It should have been called Illustreret Tidende, that’s the grandest name the eejit knows:

‘I-is it Danish?’

‘No, it’s from the mountain Himalaya, which is so high that if you climbed our mountain thirteen times, you still wouldn’t have reached the top. Halfway up the slopes of the great mountain is the parish of Darjeeling. And when the birds in Darjeeling break into their dawn chorus, life quickens on the paths that link the teagardens to the villages: it’s the tea-pickers going to their work; they may be poorly dressed, yet some have silver rings in their noses.’

‘I-is it thrushes singing?’ asks the eejit.

‘No, it’s the song sparrow, and under its clear song you can hear the tapping of a woodpecker.’

‘N-no birds I know?’

‘I expect there are wagtails,’ answers Fridrik.

Halfdan nods an

d sips his tea. Meanwhile Fridrik twists up his moustache on the left-hand side and continues his tale:

‘At the garden gate they each take their basket and the day’s work begins. From then until suppertime the harvesters will pick the topmost leaves from every plant, and their fingertips will be the tea’s first staging post on the long journey that may end, for example, in the teapot here at Brekka.’

So this morning hour passes.

It is daylight when Fridrik and the eejit Halfdan come out of the farmhouse with the coffin between them. They carry it easily; the dead woman was not large and the coffin is no work of art, knocked together from scraps of timber found around the farm – but it’ll do and seems sound enough. The mare Rosa waits out in the yard, sated with hay. The men place the coffin on a sledge, lash it down good and hard, and fasten it either side of the saddle with long spars, which lie along the horse’s flanks and are tied firmly to the sledge.

After this is done, Fridrik takes an envelope from his jacket. He shows it to Halfdan and says:

‘You’re to give Reverend Baldur this letter as soon as the funeral is over. If he asks for it before, tell him I forgot to give it to you. Then you’re to remember it when he has finished the ceremony.’

He pushes the envelope deep into the eejit’s pocket, patting the pocket firmly:

‘When the funeral’s over ...’

And they say goodbye, the man who owned Abba and her sweetheart – former sweetheart.

***

Brekka in the Dale, 8 January 1883

Dear Archdeacon Baldur Skuggason,

I enclose the sum of thirty-four crowns. It is payment for the funeral of the woman Hafdis Jonsdottir, and is to cover wages for yourself and six pallbearers, carriage of the coffin from the farm to the church, lying in state, three knells and payment for coffee, sugar and bread for yourself and the pallbearers, as well as any mourners who may attend.

I do not insist on any singing over the woman, nor any address or recital of ancestry. You are to be guided by your own taste and inclinations, or those of any congregation.

I have seen to the coffin and shroud myself, being familiar with the task from my student days in Copenhagen, as your brother Valdimar can attest.

I hope this now completes our business with regard to Hafdis Jonsdottir’s funeral service.

Your obedient servant,

Fridrik B. Fridjonsson

P.S. Last night I dreamt of a blue vixen. She ran along the screes, heading up the valley. She was as fat as butter, with a pelt of prodigious thickness.

F. B. F.

***

Now the foolish funeral procession lacks for nothing. It sets out from the yard, that is to say, it slides headlong down the slopes, until man, horse and corpse recover their equilibrium on the riverbank. One could skate along it up the valley, all the way to the church doors at Botn.

Herb-Fridrik goes into the house. He hopes that Halfdan, eejit that he is, won’t break open the coffin and peep inside on the way.

On Saturday 18 April 1868 a great cargo ship ran aground at Onglabrjotsnef on the Reykjanes peninsula, a black-tarred triple-master with three decks. The third mast had been chopped down, by which means the crew had saved themselves, and the ship was left unmanned, or so it was thought. The splendour of everything aboard this gigantic vessel was such an eye-opener that no one who hadn’t seen it for himself would have believed it.

The cabin on the top deck was so large that it could have housed an entire village. It was clear that the cabin had originally been highly decorated, but the gilding and paint had worn off, and all was now squalid inside. Once it had been divided up into smaller compartments but now the bulkheads had been removed and sordid pallets lay scattered hither and thither; it would have resembled a ghost ship, had it not been for the stench of urine. There were no sails, and the remaining tatters and cables were all rotten.

The bowsprit was broken and the figurehead degraded; it had been the image of a queen, but her face and breasts had been hacked away with the sharp point of a knife: clearly the ship had once, long ago, been the pride of her captain, but had later fallen into the hands of unscrupulous rogues.

It was hard to guess how long the ship had been at sea or when she had met with her fate. There were no logbooks and her name was almost entirely obliterated from bow and stern; though in one place the lettering ‘... Der Deck ...’ was visible and in another ‘V ... r ... ec ...’ – so people guessed she was Dutch in origin.

When this titanic ship ran aground the surf was too rough for putting to sea; any attempt at salvage or rescue was unthinkable. But when an opportunity finally arose, the men of Sudurnes flocked on board and set to in earnest. They broke up the top deck and discovered, to general rejoicing, that the ship was loaded entirely with fish-liver oil. It was stored in barrels of uniform size, stacked in rows, which were so well lashed down that they had to send out to seven parishes for crowbars to free them. This served well.

After three weeks’ work the men had unloaded the cargo from the upper deck on to shore; it amounted to nine hundred barrels of fish-liver oil.

Experiments with the oil proved that it was excellent lighting fuel, but it resembled nothing the people knew, either in smell or taste; though perhaps a faint hint of singed human hair accompanied the burning. Malicious tongues in other parts of the country might claim that the oil was plainly ‘human suet’, but they could keep their slander and envy – nothing detracted from the joy of the folk in the south-west over this windfall that the Almighty Lord had brought to their shore so unlooked for, and involving so little effort, loss of life or expense to themselves.

They now broke open the middle deck, which contained no fewer barrels of oil than the upper; and although the unloading was carried out with manly zeal, they seemed to make no impression. Then, one day, they became aware of life on board. Something moved in the dark corner by the stern, on the port side, accessible by a gangway running between the hull and the triple rows of barrels. There came a sound of sighing and moaning, accompanied by a metallic clanking.

These were uncanny sounds and men were filled with misgiving. Three stout fellows volunteered to enter the gloom and see what they should see. But just as they were preparing to pounce on the unlooked-for danger, a pathetic creature crept out from under the stack of barrels, and the men very nearly stabbed and crushed it to death with their crowbars, so great was their shock at the sight.

It was an adolescent girl. Her dark hair fell like a wild growth from her head, her skin was swollen and sore with filth; her nakedness was covered by nothing but a torn, stinking sack. There was an iron manacle around her left ankle, which chained her to one of the great ship’s timbers, and from her miserable couch it was not hard to guess what use the crew had made of her. Then there was a bundle that she held in a vice-like grip and would not be parted from.

‘Abba ...’ she said, so emptily that they shuddered, but she could give no further account of herself, despite being questioned. The salvage men realised that she was a simpleton, and some thought she looked as if she was carrying. They brought the girl and bundle ashore and delivered them into the hands of the sheriff’s wife. There she was given food and allowed to sleep two nights in a bed before being dressed in fresh clothes and sent to Reykjavik.

The salvage team was still busy on the third Sunday in June when the mail ship Arkturux rounded the cape of Reykjanes. As she passed the wreck of the oil ship, the passengers gathered at the rail to gaze at the colossus that lay stranded in the bay.

The oil porters took a break from their work and waved to the passengers, who waved back blearily, newly emerged from three days’ filthy weather north of the Faroes.

Among the passengers was a tall young man. He had a brown-checked woollen blanket round his shoulders, a grey bowler hat on his head and a long-stemmed pipe in his mouth.

He was Fridrik B. Fridjonsson.

Herb-Fridrik fills his pipe and contemplates the bundle that sits

on the parlour table where the coffin had rested an hour before. It is wrapped in black canvas and tied up with three-ply string – which has held up well despite not having been touched for over seventeen years – and measures some sixteen inches high, twelve inches long and exactly ten wide. Fridrik grasps the bundle firmly, raises it to head height and shakes it against his ear. The contents are fixed, weight around ten pounds, nothing rattles inside. Any more than it ever has.

Fridrik puts it back on the table and goes into the kitchen. He pokes a match into the stove and carries the flame to his pipe, lighting it with slow, deliberate sucks. The tobacco crackles, he draws the first smoke of the day deep into his lungs and announces to thin air as he exhales:

‘Umph belong Abba.’

‘Umph’ could mean so many things in Abba language: box, chest, casket, ark or trunk, for example.

Fridrik has long had his suspicions as to what the bundle contains – he has often handled it – but only today will his curiosity be satisfied.

***

Fridrik crossed paths with Hafdis three days after his arrival in Iceland. He was on his way home from a dinner engagement, a gargantuan coffee-drinking session and singsong at the home of his former tutor, Mr G—. He let his legs decide the route. They swiftly bore him up from Kvosin, out of town, south over the stony ground and down to the sea where he ran along the ocean shore, yelling to bright infinity:

‘I pay homage to you, ocean, o mirror of the free man!’

It was Midsummer’s Eve, flies were swinging on the stalks, a ringed plover piped and the rays of the midnight sun barred the grass.

In those days the capital was small enough that a sound-limbed man could walk around it in half an hour, so Fridrik was soon back where his evening stroll had started – on the track behind the house of the old, grey tutor, Mr G—. The cook’s son came out of the back door, taking care not to drop a tray bearing a tin cup, potato peelings, trout skin and a hunk of bread; leftovers from the feast earlier in the evening.

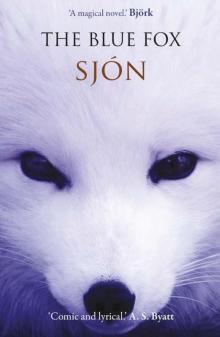

The Blue Fox: A Novel

The Blue Fox: A Novel From the Mouth of the Whale

From the Mouth of the Whale The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat and Other Stories from the North Moonstone

Moonstone CoDex 1962

CoDex 1962 The Whispering Muse: A Novel

The Whispering Muse: A Novel The Whispering Muse

The Whispering Muse The Blue Fox

The Blue Fox